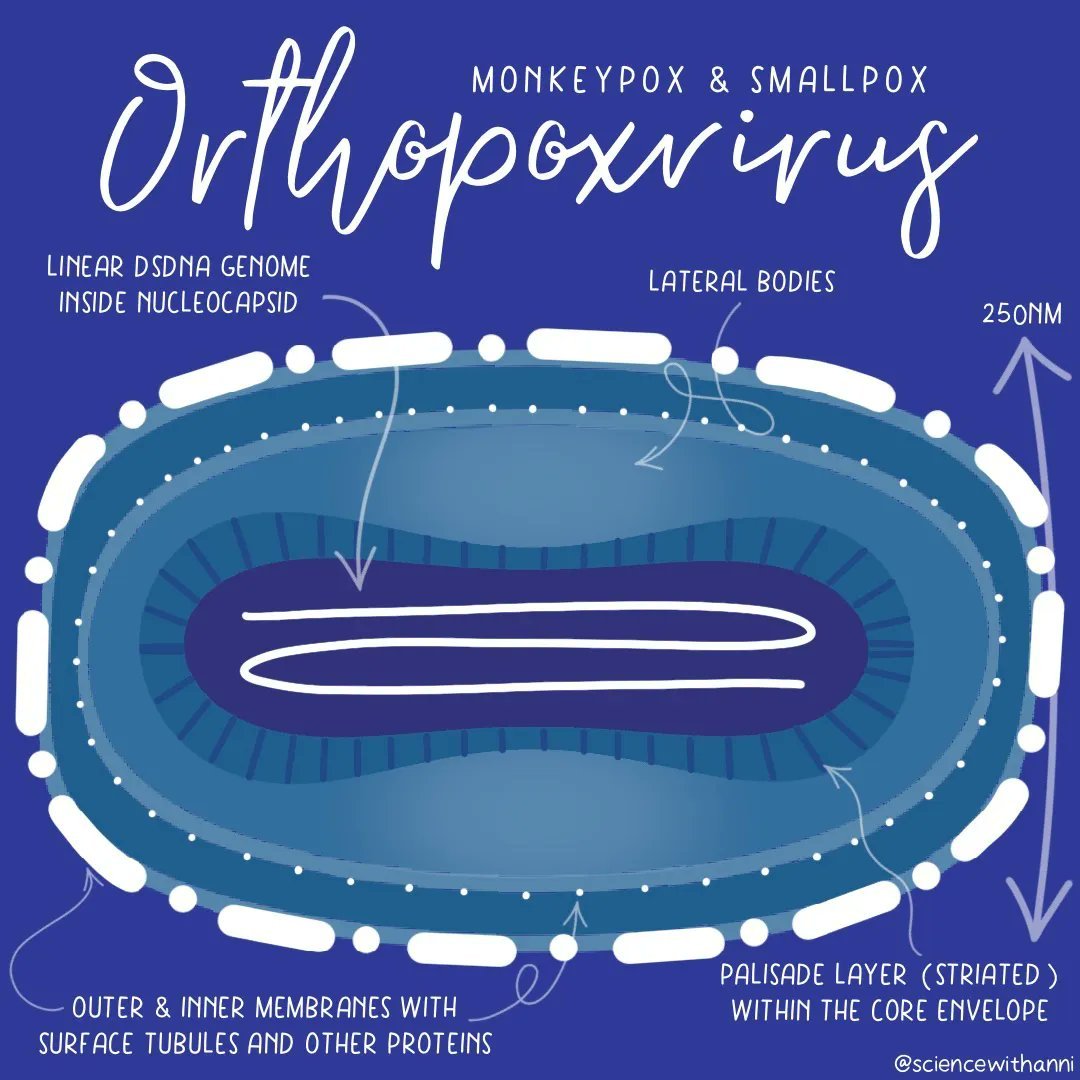

Monkeypox virus (MPXV) is a zoonotic pathogen, meaning it originates in animals and can be transmitted to humans. It is an enveloped double-stranded DNA virus with a genome size of approximately 190 kilobases (kb).

MPXV belongs to the Orthopoxvirus genus, part of the Poxviridae family. This family includes other well-known viruses like the Vaccinia virus, which is used in the smallpox vaccine, the Cowpox virus, and the Variola virus, which causes smallpox.

Historical Background and Discovery

Monkeypox was first identified in 1958 when two outbreaks of a pox-like disease occurred in colonies of monkeys kept for research. The name “monkeypox” was derived from this initial discovery, though the virus primarily circulates among rodents and other small mammals in the wild.

The first human case of monkeypox was recorded in 1970 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Since then, it has primarily been reported in Central and West Africa, although outbreaks have occurred in other regions, highlighting its potential to spread beyond its traditional endemic areas.

Variants and Clades

Through genomic sequencing, scientists have identified two distinct clades of MPXV: the Central African (CA) clade and the West African (WA) clade. These clades differ significantly in terms of virulence and transmission dynamics.

The Central African clade is generally associated with more severe disease, higher mortality rates, and more frequent human-to-human transmission. In contrast, the West African clade tends to cause less severe illness and is less likely to spread between humans.

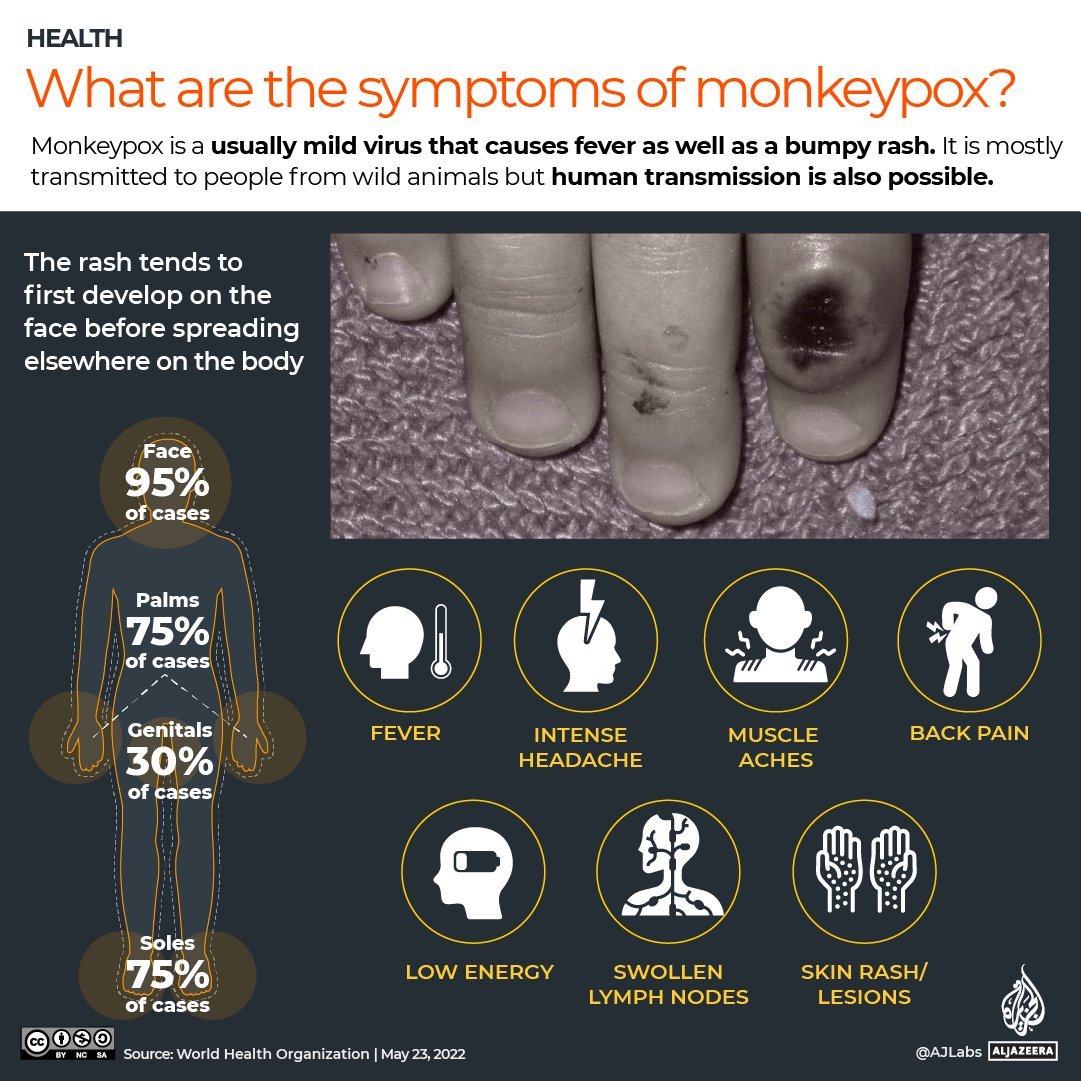

Symptoms and Incubation Period

The incubation period for monkeypox, which is the time from infection to the onset of symptoms, typically ranges from 7 to 14 days but can vary from 5 to 21 days. The illness begins with nonspecific symptoms such as fever, headache, muscle aches, backache, swollen lymph nodes, chills, and exhaustion.

One of the distinguishing features of monkeypox, compared to other poxviruses like smallpox, is lymphadenopathy—swelling of the lymph nodes, which is often noticeable in the cervical (neck) or inguinal (groin) regions.

Within one to three days (sometimes longer) after the onset of fever, a rash develops, usually beginning on the face and then spreading to other parts of the body. The rash goes through several stages, starting as macules (flat lesions), progressing to papules (raised lesions), vesicles (fluid-filled lesions), and finally to pustules, which then scab over and fall off. The entire illness typically lasts for 2 to 4 weeks.

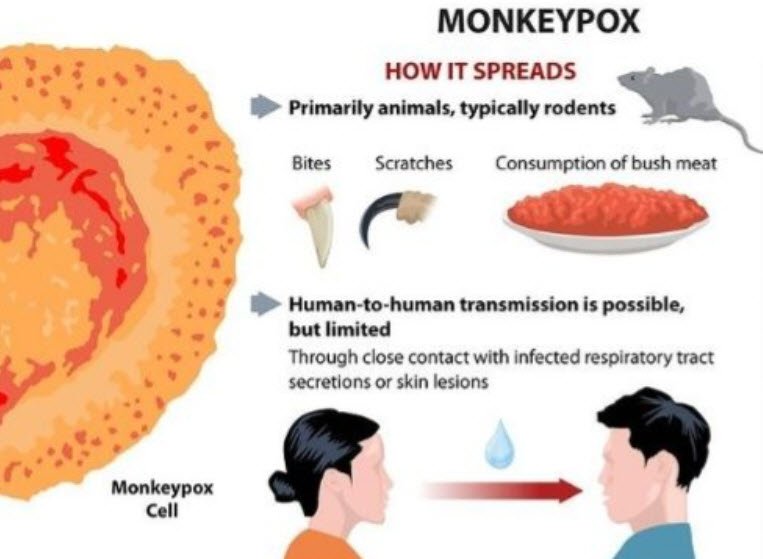

Transmission of the Virus

Monkeypox virus is transmitted to humans through contact with an infected animal or human or through material contaminated with the virus. The virus can enter the body through broken skin, even if not visible, the respiratory tract, or the mucous membranes, including the eyes, nose, and mouth.

Animal-to-human transmission can occur through a bite or scratch from an infected animal, bushmeat preparation, direct contact with body fluids or lesion material, or indirect contact with lesion material, such as through contaminated bedding.

Human-to-human transmission primarily occurs through large respiratory droplets, which generally cannot travel more than a few feet. This means that prolonged face-to-face contact is usually required for transmission. Other modes of transmission include direct contact with body fluids or lesion material and indirect contact, such as through contaminated clothing or linens. Although sexual transmission is possible, it is not the only mode of human-to-human transmission.

Diagnosis

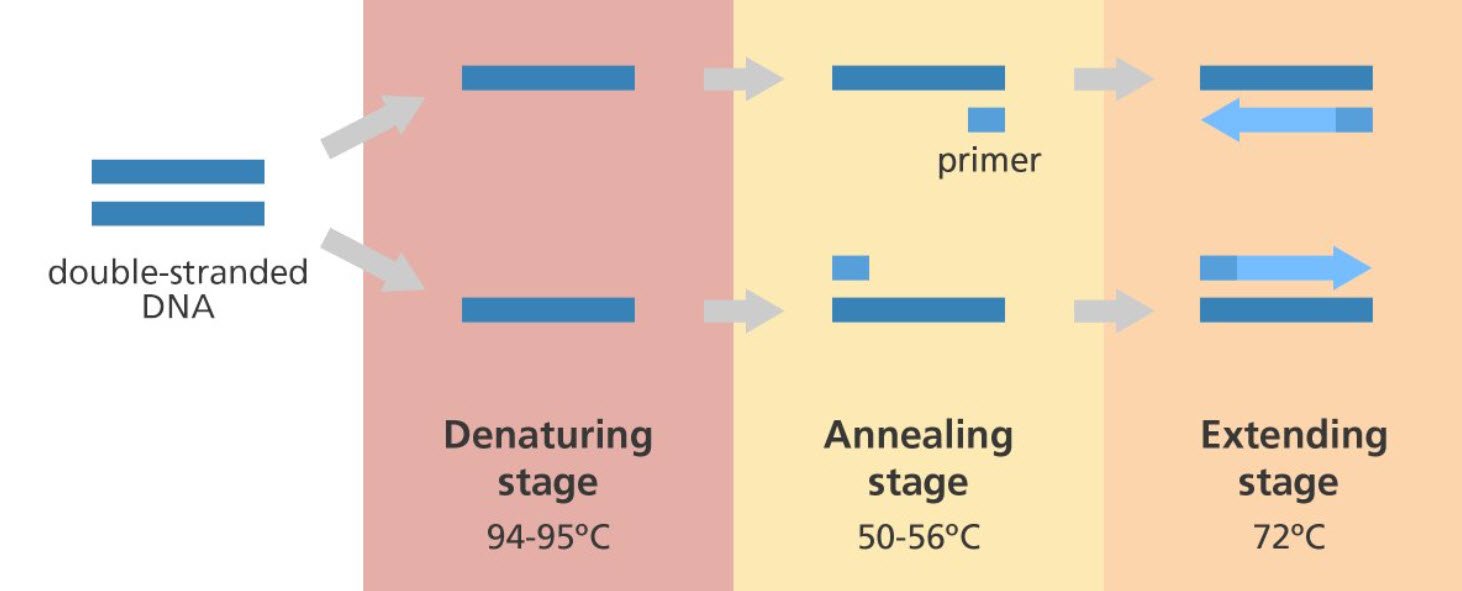

Diagnosing monkeypox typically involves the detection of MPXV DNA from suspected skin lesions using real-time PCR, also known as quantitative PCR (qPCR). This method is well-established and considered reliable.

Samples for testing are usually obtained from scabs, swabs of lesions, or aspirated lesion fluid, as these are more likely to yield positive results compared to blood samples, which may have a limited duration of viremia (the presence of viruses in the blood).

Treatment and Prevention

There is currently no specific treatment or vaccine licensed specifically for monkeypox. Treatment is primarily supportive, focusing on alleviating symptoms and preventing or managing secondary bacterial infections that might occur due to the skin lesions.

Most individuals with monkeypox experience a mild, self-limiting illness, although severe cases can occur, particularly in children, young adults, and immunocompromised individuals.

Interestingly, smallpox vaccines, particularly the first- and second-generation vaccines, have been shown to provide effective protection against monkeypox. This is because the smallpox and monkeypox viruses are closely related, both belonging to the Orthopoxvirus genus. A third-generation smallpox vaccine, known as MVA-BN (marketed as Imvanex in Europe), has been developed with a more favorable safety profile than its predecessors.

This vaccine offers cross-protection against monkeypox and has been used in recent outbreaks.

Public Health Measures and Control

The control of monkeypox, as with many other infectious diseases, relies heavily on early recognition, prompt diagnosis, and the implementation of rigorous infection prevention and control measures. Isolation of infected individuals is crucial to prevent the spread of the virus, especially in healthcare settings where close contact between patients and healthcare workers can facilitate transmission.

In the absence of a specific treatment or widely available vaccine, public health strategies focus on educating communities about the risks of monkeypox and how to avoid exposure to the virus. This includes avoiding contact with wild animals, especially those that are sick or found dead, and practicing good hygiene, such as regular handwashing, particularly after handling animals or animal products.

Conclusion

Monkeypox, though less well-known than some other poxviruses, represents a significant public health concern, particularly in regions where it is endemic. Its potential to cause severe illness, especially in vulnerable populations, underscores the importance of continued surveillance, research, and public health preparedness.

While the virus is less transmissible and generally less severe than smallpox, the re-emergence of monkeypox in various parts of the world serves as a reminder of the ongoing threat posed by zoonotic diseases and the need for vigilance in monitoring and controlling infectious diseases.